Pacific Gyre Could Be Plastic-Free by 2028

Ship tows The Ocean Cleanup’s 2016 prototype plastic collector into the North Sea for testing. (Photo courtesy The Ocean Cleanup)

By Sunny Lewis

DELFT, The Netherlands, April 5, 2018 (Maximpact.com News) – A new ocean cleanup prototype is being deployed on the North Sea today. It is one of the last steps as the nonprofit The Ocean Cleanup prepares to launch the first ocean plastics cleanup system in the Great Pacific Garbage Patch (GPGP) this summer.

Since the summer of 2016, The Ocean Cleanup has been testing a series of prototypes at its North Sea site offshore of The Netherlands.

These tests are helping the group’s workers to gain experience in deploying offshore structures and to maximize the cleanup systems’ capacity to handle the harshest conditions they could face in the Pacific Ocean.

Afloat in the Great Pacific Garbage Patch are 1.8 trillion pieces of plastic weighing 80,000 metric tons – and new research shows the situation is rapidly getting worse. These are the findings of a three-year mapping effort conducted by an international team of scientists affiliated with The Ocean Cleanup Foundation, six universities and an aerial sensor company. Their findings were published March 22 in the journal “Scientific Reports.“

The study shows the region contains up to 16 times more plastic than previously estimated, with pollution levels increasing exponentially.

“We were surprised by the amount of large plastic objects we encountered”, said Dr. Julia Reisser of the Australian Institute of Marine Science, chief scientist of the expeditions. “We used to think most of the debris consists of small fragments, but this new analysis shines a new light on the scope of the debris.”

Oceanogrpaher Laurent Lebreton of The Ocean Cleanup, lead author of the study, explains, “Although it is not possible to draw any firm conclusions on the persistency of plastic pollution in the GPGP yet, this plastic accumulation rate inside the GPGP, which was greater than in the surrounding waters, indicates that the inflow of plastic into the patch continues to exceed the outflow.”

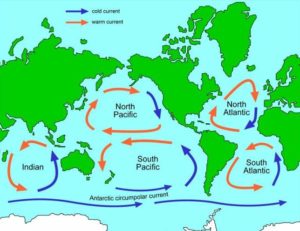

Map of the five ocean gyres of the world where ocean plastic accumulates. (Map by The University of Waikato) Posted for media use

The Great Pacific Garbage Patch, located halfway between Hawaii and California, is the largest accumulation zone for ocean plastics on Earth.

Cleaning up the Great Pacific Garbage Patch using conventional methods – vessels and nets – would take thousands of years and tens of billions of dollars to complete.

The Ocean Cleanup’s passive systems are estimated to remove half the Great Pacific Garbage Patch in five years, at a fraction of the cost. Their first cleanup system is set to be deployed mid-2018.

Here’s how it works. Instead of nets, this cleanup system is equipped with an impermeable screen to catch the sub-surface debris. Sea life can safely pass underneath the screen with the current.

Scale model tests show the screen can catch anything from one centimeter plastic particlesup to large discarded fishing nets several meters in size.

The screen is made from a tightly constructed, geotextile-inspired material that is impermeable to marine life.

The system has a floater, a two kilometer long continuous hard-walled pipe made from high density polyethylene (HDPE) a durable and recyclable material.

Togther with the screen, its purpose is to catch and concentrate plastic while providing buoyancy to the whole system.

A large sea anchor slows the system down to let it move slower than the plastic, thus capturing it.

Algorithms help specify the optimal deployment locations, after which the systems roam the gyres autonomously. Real-time telemetry will allow The Ocean Cleanup team to monitor the condition, performance and trajectory of each system.

These systems fully rely on the natural ocean currents and do not require an external energy source to catch and concentrate the plastic. All electronics used, such as lights and the AIS, an automatic tracking system used on ships and by vessel traffic services, will be solar powered.

These ocean cleanup systems are scalable. The group says, “By gradually adding systems to the gyre, we mitigate the need for full financing upfront. This gradual scale-up also allows us to learn from the field and continuously improve the technology along the way.”

“Over the past three years,” the group says, “we moved from feasibility research, to reconnaissance missions, to extensive scale model and prototype testing. We expect our first operational cleanup system to be deployed in the Great Pacific Garbage Patch by mid-2018.

“Our idea has developed and improved substantially since the first conceptual design and the feasibility study. Since there is no previous technology like ours, we believe the best way to move forward is to test fast and often to look for the things that do not yet work as planned,” the group explains.

By scaling up, researching and working together with offshore companies such as Boskalis, SBM Offshore and Heerema and institutes, including IMARES, Deltares and MARIN, we believe initiating the cleanup by mid-2018 is achievable, the group says.

Boyan Slat, founder of The Ocean Cleanup and co-author of the GPGP study, said, “To be able to solve a problem, we believe it is essential to first understand it. The results provide us with key data to develop and test our cleanup technology, but it also underlines the urgency of dealing with the plastic pollution problem. Since the results indicate that the amount of hazardous microplastics is set to increase more than tenfold if left to fragment, the time to start is now.”

The major gyres of the ocean are located in the North Atlantic, South Atlantic, North Pacific, South Pacific and Indian Ocean.

Ocean gyres in the Northern hemisphere rotate clockwise and gyres in the Southern hemisphere rotate counter-clockwise due to the Coriolis effect, and both types gather plastic marine debris.

As most everyone in the world knows by now, plastic debris is a serious threat to marine animals. While large pieces of litter can have big impacts on marine animals, less obvious are the dangers of plastics measuring less than five millimeters in size, known as microplastics. These tiny bits of debris are affecting some of the planet’s largest animals.

Baleen whales strain thousands of gallons of water each day for plankton, small fish, or crustaceans. Not only does their filter feeding behavior enable them to consume microplastics, reportedly by the thousands per day, but because most whales have a thick blubber layer, fat-soluble chemicals leached from the plastics can be readily absorbed into their bodies.

Other marine mammals, such as dolphins, porpoises, seals, and sea lions can also be affected. If the small fish and other prey they consume have themselves consumed microplastics, the debris can accumulate as it makes its way up the food chain.

In a recent study scientists found 83 percent of observed oceanic-stage loggerhead sea turtles in the North Atlantic had plastic in their gastrointestinal tracts. Plastics ranging from one to five millimeters in length were noted in 58 percent of individuals. This is especially bad news for sea turtles, as all seven species of sea turtles are endangered or threatened.

Although it’s not an ocean gyre, the Mediterranean Sea, too, is greatly affected by marine litter. In this area, research on the impact of plastic debris on large filter-feeding species such as the fin whale is still in its infancy.

Though removal is an important piece of the puzzle, prevention is the ultimate key. By working to prevent marine debris through education, outreach, and making an individual effort to reduce our own contributions, we can put a stop to this global concern.

Featured image: A live leatherback turtle entangled in fishing ropes, Grenada 2014. (Photo by Kate Charles, Ocean Spirits) Posted for media use.