Problematic Chicken Feathers Solve Modern Problems

ZURICH, Switzerland, October 23, 2023 (ENS) – Scientists are finding innovative ways of turning waste into problem-solving products – even the 102 million tonnes of chicken feathers produced globally each year by the industrial processing of chickens for meat. The waste feathers have been sent to landfills, requiring costly waste management systems, or incinerated, releasing harmful gases. But now there are ways to transform waste feathers into valuable products from fuel cell membranes to oil spill dispersants.

Take the work that two teams of scientists on the opposite sides of the globe are doing together. Researchers at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zurich (ETH Zurich) and another team at the Nanyang Technological University Singapore (NTU) have found a way to put these waste feathers to good use in a high-tech industry.

Chicken feathers are 91 percent keratin, a protein also found in animal hair, hoofs, horns, and wool. Left in a landfill, chicken feathers usually take five to seven years to disintegrate because of the keratin component in them.

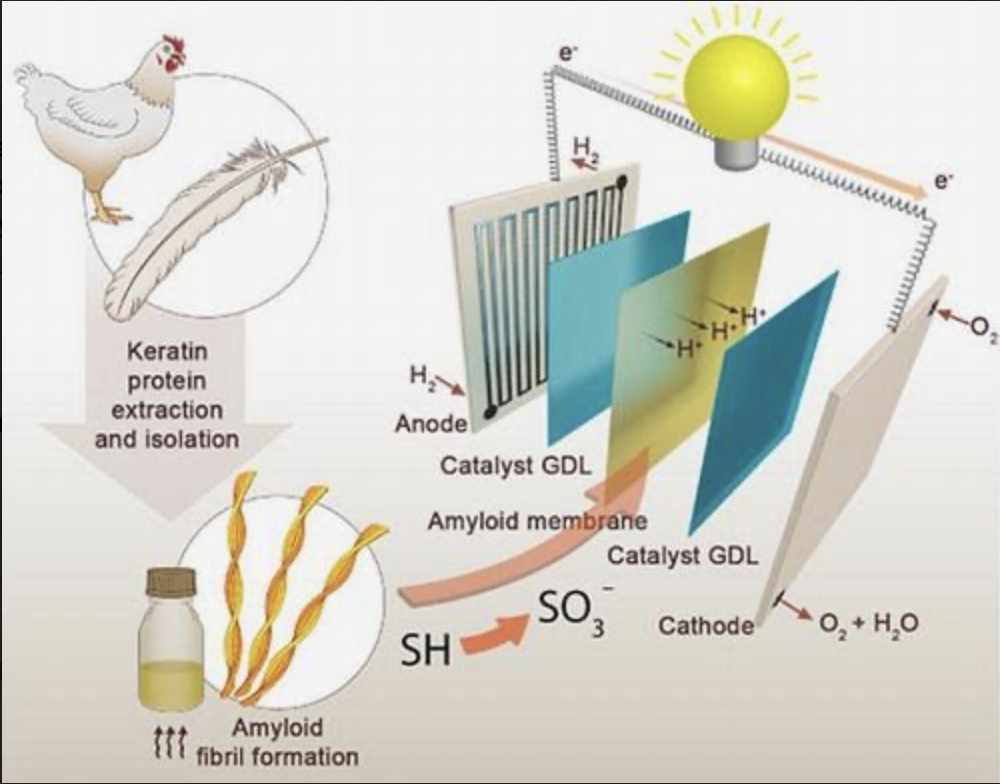

This week, the scientists at ETH Zurich and NTU published <https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsami.3c10218> their discovery of a simple and environmentally friendly process to extract the protein keratin from the feathers and convert it into ultra-fine fibres known as amyloid fibrils. These keratin fibrils can then be used in the membrane of a fuel cell.

Fuel cells generate electricity from hydrogen and oxygen, emitting only heat and water, sustainable because they emit none of the greenhouse gas carbon dioxide. They are CO2-free.

At the core of every fuel cell lies a semipermeable membrane. It allows protons to pass through but blocks electrons, forcing them to flow through an external circuit from a negatively charged anode to a positively charged cathode. This flow of electrons produces an electric current.

In conventional fuel cells, these membranes have been made using toxic chemicals, which are expensive and don’t break down in the environment.

But the new membrane developed by ETH and NTU researchers consists mainly of biological keratin, which is environmentally compatible and available in large quantities. This means the membrane manufactured in the lab from chicken feathers is up to three times cheaper than conventional membranes.

“I’ve devoted a number of years to researching different ways we can use food waste for renewable energy systems,” says Raffaele Mezzenga, professor of Food and Soft Materials at ETH Zurich. “Our latest development closes a cycle.”

Each year, some 40 million tonnes of waste chicken feathers are incinerated globally, releasing the greenhouse gas carbon dioxide (CO2), and producing toxic gases such as sulphur dioxide (SO2).

“We’re taking a substance that releases CO2 and toxic gases when burned and using it in a different setting. With our new technology it not only replaces toxic substances, but also prevents the release of CO2, decreasing the overall carbon footprint cycle,” Mezzenga said.

But hydrogen must be manufactured before it can be a sustainable energy source.

“Hydrogen is the most abundant element in the universe – just, unfortunately, not on Earth,” Mezzenga explained.

Since hydrogen doesn’t occur here in its pure form, it has to be produced by splitting water (H2O), which has required a great deal of energy. Here, too, the new membrane could serve well in the future, because it can be used not only in fuel cells but also in water splitting. Protons can pass through the keratin-based membrane, so it enables the particle migration between anode and cathode necessary for efficient water splitting.

The researchers’ next step will be to investigate how stable and durable their keratin membrane is, and to improve it if necessary. A patent is pending. The research team already has filed a joint patent for the membrane and is now looking for investors or companies to develop the technology further and bring it to market.

Oil Spill Dispersants

In September, seven scientists from the University of Ghana in the African country’s capital city Accra published <https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10536068/> their work to formulate an environmentally benign dispersant made from chicken feather protein that is capable of crude oil dispersion in the marine environment.

Toxicity of oil spill dispersants is a major concern, and several dozen studies from the years 2003 through 2022 have shown that dispersants can compound the toxic situation created by the initial oil spill.

Many, but not all, dispersants have been shown to be lethal to cells cultured in the lab, suggesting that they are toxic to larger animals as well, Richard S. Judson, a chemist with the U.S. EPA’s National Center for Computational Toxicology, said back in 2010.

These chemical dispersants can persist in the water column for years, rather than break down quickly as predicted, warned Dr. Helen K. White, in 2014. Her research explores the persistence of human‐derived compounds in the marine environment.

In their newly published study, the Ghanaian scientists explain, “To eliminate the subject of toxicity, there exist several materials in nature that have the ability to form good emulsions, and such products include protein molecules. In this study, chicken feathers, which are known to contain more than 90 percent protein, were used to formulate a novel dispersant to disperse crude oil in seawater.”

Protein from chicken feathers was extracted and synthesized into the chicken feather protein dispersant using deionized water as a solvent.

The chicken feather protein surfactant was tested for toxicity on fish, specifically Nile tilapia, by measuring the lethal effect after a 96 hour exposure. The results showed that the CFP dispersant is environmentally friendly, the Ghanian scientists concluded.

Flame Retardant Boosters

Earlier this year, scientists in the Mechanical Engineering Department at the University of Auckland in New Zealand published <https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1359835X2200519X#:~:text=The%20global%20chicken%20feather%20production,to%20the%20adverse%20environmental%20effect> their work on the repurposing of chicken feathers by turning them into flame retardant boosters.

These boosters enhance retardancy in phosphorous-based flame retardants, a class of retardants is used to improve the fire safety of flammable materials such as plastics, textiles, wood, and paper.

They, too, learned that using chicken feathers this way can lower industrial waste volumes, thus avoiding expensive waste management solutions.

Meanwhile, lowering the amount of expensive phosphorous-based flame retardants needed to improve safety of the flammable materies has cut the cost of manufacturing flame-retardant composites.

Biodiesel From Feathers

In 2018, scientists from three universities in India published the fruits of their collaboration on the development of biodiesel production using chicken feather meal as a cost-effective feedstock by using green technology.

Researchers from Thiruvalluvar University, Sri Abirami College for Women, and Bharathiar University, all in the the southernmost state of Tamil Nadu, described a new and environmentally friendly process for developing biodiesel from commercial feather meal.

Their paper <https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2405580818300219> describes a new and environmentally friendly process for developing biodiesel from commercial feather meal.

“Chicken feather meal, which is a waste ingredient of poultry processing unit, provides us a new cheap raw material to produce biodiesel.

“In this work, we have extracted fat from the feather meal in boiling water (70 °C) and then transesterified the fat into biodiesel using KOH and methanol; 7−11% biodiesel (on a dry basis) is produced in this process,” the Indian researchers wrote.

Feeding Chicken Feathers to Chickens, Maybe Humans Too

Given its high protein content, feather meal is used as a feed for farm animals, including chickens. To make animal feed, the feather meal is hydrolyzed, a process of cooking the feathers with steam that breaks down the protein source into the tiniest possible particles.

Treating chicken feathers with a dilute sodium hydroxide solution and pressure cooking the mix resulted in the best quality chicken feather meal for feeding broiler chickens, according to a 2013 study by scisntists at Indonesia’s Padjadjaran University.

Chicken feather meal is used also as an organic fertilizer. Because of its high nitrogen content, it is considered great for nitrogen-needy crops, trees, and flowers.

But Would You Eat It?

Now, Sorawut Kittibanthorn, a researcher and designer from Thailand who studied for a Masters of Material Futures in London, UK and in the Netherlands, is experimenting with using chicken feather meal for human food.

Writing in “The Future Materials Bank,” part of Future Materials, an initiative of the Nature Research Department at the Jan van Eyck Academie based in Maastricht, Netherlands, Kittibanthorn said, “This project proposes an alternative way to manage the 2.3 million tonnes of EU feather waste from slaughterhouses by converting its nutrient component into a new edible product.”

“Chemically, chicken feathers are composed of approximately 91% protein (keratin) which contains up to eight types of essential amino acids that we require as part of a healthy diet. It has been proven that keratin protein from feathers is safe for general consumption within our daily diet,” Kittibanthorn wrote.

By extracting these essential proteins from the feathers, Kittibanthorn has developed a new “melt-in-the-mouth” food product that is “completely safe, light in calories and provides us with the essential amino acids we require in daily life. Other advantages include reducing the carbon footprint and reconsidering how we categorise “waste.”

Take caviar, for instance. Kittibanthorn writes, “The idea is to turn the caviar farming industry into something more akin to the commercial by using keratin protein from invaluable chicken part into Everyday caviar which is more abundant, more affordable, and more accessible to all. Notably, it saves endangered wild sturgeon from being hunted to extinction!”

“Through consuming edible feathers we may pioneer a food culture that symbolises self-development and presents an empathetic response to the world. Which works towards developing a new food culture that expresses social belonging and cultural identity.” Kittbanthorn considers chicken feather meal “a tool towards achieving a sustainable future.”